©Copyright Legal Women Limited 2025

Legal Women c/o Benham Publishing Limited, Aintree Building, Aintree Way, Aintree Business Park Liverpool, Merseyside L9 5AQ

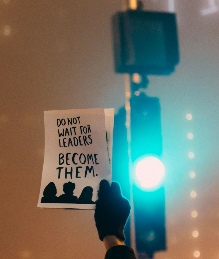

Leadership - how to get gender balance to stick?

A growing body of evidence shows that women make excellent leaders(1). Recent research has even suggested that women leaders outperform men in corporate 360 reviews(2) and that governments led by women have tended to see lower Covid-19 mortality rates(3). Of course, there are complex facts behind these stories, and we should be wary of any argument that suggests all women are A or all men are B. (On a planet of 7 billion people, it is unlikely that any such generalisation will be true - need we look further than former Tokyo Olympic chief Yoshiro Mori’s assertion that women talk too much?(4) Celebrating women’s leadership has never been a call for a female majority on decision-making bodies, but for gender balance. Against this backdrop, this article will ask what organisations can do to get better at identifying leaders and achieve gender balance in senior roles.

A growing body of evidence shows that women make excellent leaders(1). Recent research has even suggested that women leaders outperform men in corporate 360 reviews(2) and that governments led by women have tended to see lower Covid-19 mortality rates(3). Of course, there are complex facts behind these stories, and we should be wary of any argument that suggests all women are A or all men are B. (On a planet of 7 billion people, it is unlikely that any such generalisation will be true - need we look further than former Tokyo Olympic chief Yoshiro Mori’s assertion that women talk too much?(4) Celebrating women’s leadership has never been a call for a female majority on decision-making bodies, but for gender balance. Against this backdrop, this article will ask what organisations can do to get better at identifying leaders and achieve gender balance in senior roles.

Where are we on gender balance in leadership?

Earlier this year, the Hampton-Alexander review completed a five-year programme aimed at having women occupy one third of positions on FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 boards(5), but the target was missed by 32% of FTSE 100 and 39% of FTSE 250 companies(6). In fact, research from Cranfield University suggests that women in non-executive directorships are flattering the statistics - with women in executive roles hitting only 13.2% and 11.3% of FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 positions, respectively(7). By comparison, the legal sector is particularly good at recruiting women, with 60% of new solicitors since 2014 being women(8). But the challenges are in keeping with those across the economy and research by Thomson Reuters found that women made up 36% of non-equity partners and only 22% of equity partners in 2019(9). In other words, progress is being made, but more is needed.

What do organisations look for in leaders?

All organisations rely on processes to recruit and promote. Research suggests that organisations struggle to create processes that are truly gender-neutral, resulting in the trend towards gender imbalance higher up organisations. Organisational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic has popularised this research by asking the tongue-in-cheek question, ‘Why do so many incompetent men become leaders?’(10) (His real question is, ‘How can we find ungendered performance criteria?’, but I can accept that this is less catchy). His research focuses on the allure of charismatic individuals (particularly since the mediatisation of leadership since the 1960s - think JFK) and decision-makers’ linked inclination to prefer confidence over competence(11). I particularly enjoyed his lament that there will never be a biopic of Angela Merkel going to meetings well-prepared, listening to others talk and making rational decisions after long periods of consultation and reflection.

It’s all about the process

He points to the uncomfortable conclusion that, despite best intentions, workplace processes are gendered. If we understand the different expectations that men and women face in the workplace, we will be able to design more objective processes. For example, research by organisational behaviour expert Dr. Elena Doldor of Queen Mary University has found that men get more actionable feedback than women in terms of progression. Examples of this in the research were men being encouraged to ‘be visionary’, where women were encouraged to ‘execute other people’s vision’; men were encouraged to ‘be assertive’, whereas women were encouraged to ‘be cooperative and deferential’(12). This may be linked to other research by ESADE’s Associate Professor of People Management Laura Guillén, which shows that while it is professionally acceptable for men to seek a promotion for the sake of the promotion, women’s ambition is more likely to be accepted if it is tempered with stereotypically feminine traits such as empathy or altruism(13).

Action: Managers should be encouraged to review performance feedback and, if a gender gap is identified, discuss it with the evaluators on their team and make a plan. Managers should be able to find objective, ungendered markers of performance that work for their teams.

Law firms should also be conscious of the fact that, as solicitors develop, they may focus on technical and client relationship skills before addressing leadership skills. Only 1-2% of solicitors are made partner each year(14), a small percentage of whom will go on to become a head of department, and a smaller percentage still will become managing partner or senior partner. In their new podcast Leading Professional People, Cass Business School Professor Laura Empson and former Allen & Overy Senior Partner David Morley suggest that this could lead to professionals being reluctant to think of themselves as leaders. This is consistent with the research of London Business School organisational behaviour Professor Herminia Ibarra, who argues that becoming a leader is not simply a transition in responsibility, but a transition in identity(15). This transition is particularly important for women, who have to navigate their way to an ‘acceptable’ brand of leadership - “whether rejecting stereotypically masculine approaches because they feel inauthentic or rejecting stereotypically feminine ones for fear that they convey incompetence.”(16)

Action: Offer training to encourage workers to think about leadership before it is needed. This will give potential leaders time to grow into a leadership identity, both in how they see themselves and in how they are seen by others.

When do organisations look for leaders?

In law firms, solicitors who make partner tend to do so with around ten years of post-qualification experience(17). As competition for training contract places has increased, so has the average age of newly-qualified solicitors - to 29 in 2019(18). By comparison, the average age of first-time parents in the UK was 30.6 for mothers and 33.6 for fathers in 2018(19). To the extent that workers are considering having a child, this timing is difficult to navigate. Waiting to be in a position of power before taking parental leave may take too long, compounding the pressure over deciding how to share responsibility for caregiving, especially during the earliest years of a child’s life.

Pre-pandemic, policies offering an alternative to a full week in the office (often to integrate caregiving responsibilities) were taken up by women in the majority of cases. Unfortunately, the result of this gender imbalance has been a stigma which impacts all parents - for mothers, a career break, period of part-time work or different start and finish times can be viewed as socially acceptable but incompatible with leadership roles;(20 21), for fathers, there has been a reluctance to take up these policies in the first place(22).

However, positive change can happen suddenly. Only a handful of years ago, fathers might be offered two weeks of unpaid leave upon the birth of their child. Now, it is not so uncommon to take six months of paid leave, with an increasing number of employers stepping up to align parental rights between mothers and fathers. The great hope of equalising parental leave is, firstly, that it will allow fathers to have a more fulfilling family life (which is reported as being increasingly important to men with every generation)(23) and, secondly, that it will normalise taking time off work - be it parental leave, annual leave or the weekend. This could be a healthy countermeasure for a multitude of reasons: in a sector with workstreams initiated by clients (sometimes unpredictably), where billing more hours can help to make a case for promotion and where responsiveness at anti-social hours might encourage client loyalty, the pressure to be constantly available can be difficult to resist(24). As awareness increases of the impact of high workloads in professional services more widely(25), the dialogue around career goals and life goals is likely to continue(26).

Action: Gender neutralise policies around parenting. Alongside normalising taking parental leave or working part-time for a period, for example, organisations should also widen their leadership identification window to include workers who may be reaccelerating their careers after the most intense period of caregiving responsibility has passed. After all, raising the next generation is a collective project that all of society has a stake in - that includes organisations and, of course, both parents. Part of that responsibility has to be providing jobs that are compatible with caregiving; the economy is better off if it is possible to earn (and thus pay tax) and care at the same time.

Concluding remarks

Gender imbalance is not inevitable, but it is sticky and current infrastructure is seen to favour men without caregiving responsibilities across the economy. Organisations need to make gender balance stickier than imbalance. They can achieve this by collecting data to find out if systems are having unintended consequences, experimenting with new processes, keeping what works, ditching what does not and repeating. Ensuring that policies designed to help parents are applied equally to mothers and fathers is a key step to reframing the conversation around parenting and the workplace. In the future, we can hope that parental leave will be seen as a temporary step in a long career path. Mothers will benefit by advancing in organisations (with increased earnings, pensions, independence and tax receipts), while families will benefit from having more time with their partners and fathers (92.6% of fathers with dependent children in the UK were in work in 2019.(27)) As the generation of solicitors who qualified during the financial crisis reach partnership, it will be interesting to see how this new generation will rise to the challenge and what their vision for law firms in the future will be.

Helen Broadbridge, Tax Solicitor – Helen Broadbridge | LinkedIn

Views expressed are those of the author.

Photo credit Rob Walsh, Unsplash.com

1 Wittenberg-Cox, Avivah (2021), Data shows women make better leaders, Forbes.

2 Zenger & Folkman (2019), Research: Women score higher than men in most leadership skills, HBR.

3 Tett, Gillian (2020), How have countries led by women coped better with Covid-19?, Financial Times.

4 Inagaki & Harding (2021), Tokyo Olympics chief resigns over sexist remarks, Financial Times.

5 Thomas, Dan (2021), UK companies pressed to appoint more women executives, Financial Times.

6 The Hampton-Alexander Review 2021. The Hampton-Alexander Review

7 Vinnicombe, Sue (2020), Female FTSE Board Report (press release), Cranfield University.

8 Bowcott, Own (2019), Blacklaws: “It’s deplorable there aren’t more top women in law”, the Guardian.

9 Case & Hart (2019), Transforming Women’s Leadership in the Law, Thomson Reuters.

10 Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas (2019), Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? (And how to fix it), Harvard Business Review Press.

11 Chamorro-Premuzic (2021), If women are better leaders, then why are they not in charge?, Forbes.

12 Doldor, Wyatt & Silvester (2021), Research: Men get more actionable feedback than women, HBR.

13 Thomson, S. (2018), A lack of confidence isn’t what’s holding back working women, The Atlantic.

14 Connelly, Thomas (2016), Ten years to the top: average time to partnership revealed, Legal Cheek. “Just 1% of magic circle solicitors were made partner this year. This figure rose - ever so slightly - to 1.2% across the rest of London, and 1.6% at West End firms. Midlands firms offers the best chance of promotion, with 1.8% of lawyers elevated to partnership.”

15 Ibarra, H, Ely, R & Kolb, D (2013), Women Rising: The Unseen Barriers, HBR Press.

Ibid.

16 Connelly, Thomas (2016), Ten years to the top: average time to partnership revealed, Legal Cheek. “The research revealed that 80% of those handed fresh promotions had between nine and 13 years’ post-qualification experience.”

17 The Junior Lawyers Division (2019), Twenty-nine is the magic number as the average age of qualifying solicitors increases, LawCareers.

18 Office of National Statistics, Births by parents’ characteristics in England and Wales (2018).

19 Zalis, S. (2019), The Motherhood Penalty: Why we’re losing our best talent to caregiving, Forbes.

20 Wittenberg-Cox, A. (2020), 5 gender balance myths most men (and women) still believe, Forbes.

21 Churchill, Francis (2019), Fathers struggle to get the flexible work they need, People Management. “Almost 3 in 10 mothers (28.5%) with a child aged 14 years and under said they had reduced their working hours because of childcare reasons. This compared with 1 in 20 fathers (4.8%).”

22 Dinwiddy, I. (2021), Why supporting new dads in the workplace is key to gender equality, HR Zone.

23 Ely & Padavic (2020), What’s really holding women back, Harvard Business Review. “Our findings align with a growing consensus among gender scholars: What holds women back at work is not some unique challenge of balancing the demands of work and family but rather a general problem of overwork that prevails in contemporary corporate culture.”

24 Armstrong, R (2021), Junior Goldman Sachs bankers complain of 95-hour week: Group of first-year analysts send slide deck to management calling for reforms to reduce workload, Financial Times.

25 Schulte, Brigid (2018), You can be a great leader and also have a life, Harvard Business Review.

26 Office for National Statistics (2019), Families and the labour market.

27 The Junior Lawyers Division (2019), Twenty-nine is the magic number, LawCareers.